Underrated but Critical Start-Up Success Factors: Trust and Loyalty

Apr 27, 2017 · 18min read

How trust and loyalty within the leadership team can determine the success or failure of a start-up. Based on a true story.

In late 2012, I co-founded a company called EntrePreneurs (no, not really—I changed the name for this article). While my long-time business partner adopted the role of CEO, I took on the role of CIO. We were off to a good start as our first year, 2013, was financially more successful than budgeted and our team had quickly grown to the size required to reach the goals laid out in our business plan. At the beginning of our second year, in March 2014, we were just two months away from being on the winning side of a referendum that had been the last obstacle to our first big public-private partnership.

Paradoxically, this was also the time when we had to shut down the company—and fire all 16 people in the process including ourselves, the founders.

Now, three years later, I would like to look back and share my experience and learnings with you: How or why could happen what had happened to EntrePreneurs? What do I think were the main reasons for EntrePreneurs to fail the way it did? What could we have done differently to save the company and be successful?

The motivation for this article is twofold. On the one hand, I want to take notes of my memories (I find myself forgetting already some of the details) and clarify some misconceptions. On the other hand, I simply want to allow others to learn and benefit from our mistakes. Or as the German saying goes:

Everything is good for something—and be it to serve as a bad example.

German proverb

The Obvious Reason for Bankruptcy ¶

Before going any further into detail, let me set the record straight regarding the only reason we had to close EntrePreneurs down: We simply ran out of money.

Of course, several events led to the result (see next section below); but in the end, it quite simply came down to lack of liquidity. This might be stating the obvious after going bankrupt—but one rather popular misconception is that the burn-out of my business partner, the EntrePreneurs’ CEO, was the main reason behind the shut-down.

It was not.

Let me explain: While the company’s looming bankruptcy and the CEO burning out certainly aggravated each other in a vicious circle, I believe by now that both were symptoms of a much deeper, common root cause.

To give you the context of why the financial situation could develop the way it did in the first place, let me paint the bigger picture:

When a Calculated Risk Becomes an Existential Threat ¶

Knowingly Underfunded Business Plan ¶

We launched EntrePreneurs with ~70% of the funds required to break even according to our business plan. We were all confident that we would be able to close the gap during the first year (and to some limited extent we were able to deliver on this promise). Our experienced investors and the seasoned business managers on our supervisory board did not seem to be overly worried about the gap—in the beginning at least. In other words: We accepted the initially underfunded business plan as calculated risk.

As it turned out, it was quite difficult and hence took longer to find investors for a Series B funding. For the first venture round, we had been able to rely on existing partnerships established over several years; for the second round, we had to forge new relationships with people who were unfamiliar with our approach and our social business model. You should know: EntrePreneurs was not just a start-up trying to disrupt an existing industry; as a service provider for not-for-profit organizations (NGOs) in Switzerland, we were a new company in a new industry. There was nobody outside EntrePreneurs who already had experience in this area, let alone as a start-up investor. Naturally, it took a lot of time and work to find potential investors.

If your business plan requires funds from still unknown third parties, account enough time for building those relationships. It’ll take longer than you think.

Involuntary Political Discourse ¶

This calculated risk of the underfunded business plan eventually turned into an existential threat due to an unforeseen circumstance that unfolded in parallel. We were making big strides in the public sector and were invited to participate as consultants in the revision of a law in the canton of Lucerne. (Cantons in Switzerland are what states are in the US.) The idea behind said revision was to extend public-private partnerships in exactly our domain—a really big deal for our company.

Unfortunately, some political factions opposed the approach envisioned in the draft—and, in good Swiss tradition, started a referendum against the new law. This had two significant effects:

- Lots of public exposure, interviews, debates, and lobbying suddenly became necessary to an extent that we were not at all prepared or equipped for. It certainly did not help the health of our CEO.

- It stalled the political process and hence our business development in that domain. Investors that had shown interest now naturally wanted to wait and see how the referendum would pan out. After all, it could set precedent for the other 25 cantons as well and thus determine if this integral part of our business plan would hold.

In case you plan a start-up based on private-public partnerships in Switzerland: Make sure you have a referendum strategy in place.

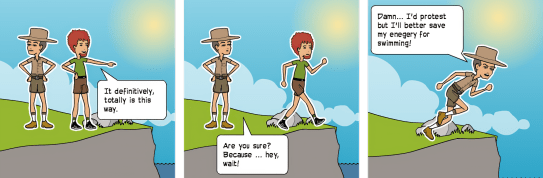

At some point, it became clear that the result of the referendum would come in roughly two or three months after our liquidity would dry up. We could not wait for new investors much longer, but new investors wanted to wait for the result of the referendum first. We were trapped, and in my firm opinion, no healthy CEO could have solved this conundrum.

It did not matter that in the end, the referendum was decided by 70% in favor of the new law. Our calculated risk already had become an irrecoverable error.

Let me cut the story short by saying that we, of course, tried to rally all existing investors and indeed were able to reduce the delta from three months down to two. We also calculated scenarios in which we would fire all non-essential personnel to cut down our main cost driver and thus squeeze out two more months—just to confirm that we already were a lean company with essential personnel only. So yes, irrecoverable error after all.

If Bankruptcy and Burn-Out Both Are Symptoms—What Is the Root Cause? ¶

Let us assume for a moment that starting with the gap in our initial funding indeed was the right choice. What else went wrong early on—or could we have done differently to be successful? Probably there are tons of answers to those questions, but I believe to know one very good answer that goes to the core:

Too little trust and too much loyalty within the leadership team. Yes, with the leadership team I am referring to the two managing co-founders—which includes myself. So the following parts A and B also are a self-critical reflection.

A Bit of Personal History ¶

To understand the point I am trying to make with this article, one first needs to roughly know the background of the two of us.

We knew each other since high school and were very good friends for many years. Eventually, we launched and started working on a project along with a few other people. Especially in the beginning, our relationship provided rock-solid continuity that was essential to the project’s success. Many others joined and left the project management over time; but we stayed, carried on and, after three years, turned the project into serious jobs for us. The two of us shared the same core values and our communication as well as decision making were quite efficient—we did not need many words to perfectly understand each other. One being the economics and strategy guy, the other being the IT and media guy, our skill sets complemented well.

When the time came to found a company around the project, some of the investors insisted on making sure that the two of us would keep the final say. It was a testament to the good team we were.

Part A: Growing a New Business Requires Growing Trust ¶

Putting together the right team is high on the list of top challenges for any company—even more so if you start a new business that requires to scale quickly to a certain level in more than one domain.

It was clear early on that we soon would require to extend the management team (finance and operations), too. But we never got to hiring anyone for these jobs—other than in a late and somewhat desperate reaction to the CEO’s burn-out.

On the one hand, externally, it was difficult to find a lot of candidates in the open market that would be bold enough to embark on our journey—in a new company in a new industry with moderate salaries. On the other hand, internally, the constellation of having a close relationship between the existing leadership team made things even more difficult for outsiders.

At some point, it dawned on me that the close relationship between CEO and CIO was quite literally too close, as in closed. We would need to open up and trust outsiders more.

As the perfectionist he was, our CEO demanded only the best from him and also everybody else. And while these high expectations can push a team to deliver outstanding work, it can also trap you. Naturally, as CEO, there were many things that he was more successful at than other people. But even after delegating duties to others, he often found himself right back in the middle of the delegated tasks as soon as things took a direction he thought was the wrong way.

I admit that trusting somebody else vs. executing a task yourself can be a powerful dilemma. How can you as CEO of a small new company remain in a zoomed-out steering position when people in the field make mistakes that are costly to your business and narrow your overall chance of success? The smaller the margin of error (in our case small due to the underfunded business plan), the more powerful the dilemma.

Then again, the company was not so small either. Our headcount quickly went beyond ten so it was impossible for one person to simultaneously fulfill the job of everybody else. The only option should have been trusting the team, allowing it to learn and grow through mistakes. Yet, what happened was that the CEO stopped taking the necessary breaks; after-work hours, weekends and vacations more and more became rarities as he was trying to keep everything and everyone aligned, ready to intervene at any time. Talk about burn-out.

Don’t just manage your time. Manage your energy.

A frequent response to this line of reasoning is that then, obviously, the team must have been not good enough. I understand this impulse but here is the deal:

- There is no objective comparison available to draw this conclusion from. We had no competitors, much less one that would have out-performed us.

- Subjectively, I would argue that the people on the team were highly and intrinsically motivated and had a strong inner drive. (At least, nobody came for the money as our salaries were moderate compared to the high expectations.)

- Just like anywhere else on this planet, the people on the team were hired based on a sweet spot between skills and availability. You only can hire the best people available or wait until someone better comes along—but how much waiting time can you afford as a start-up?

- In the end, the CEO is accountable for recruiting the best team available. If a CEO has to do the job of his team, he has failed at his job and needs to correct the situation on his end. Harsh but true.

The irony is that with a perfectionist CEO the team constantly receives the feedback of not delivering well enough, fast enough—and eventually starts to believe that it is not the best team. It even starts to rely on the mechanism that if things go wrong, somebody will swoop in and save the day anyway.

While I definitively think that the people we had on the team were the right ones, I feel that the CEO’s (too) high standards prevented us from adding another manager to the leadership team soon enough to make a difference concerning our underfunded business plan. The real turning point or backbreaker in hindsight for me was when our CEO decided to cancel talks with a candidate in the middle of contract negotiations. Instead of welcoming a third manager that immediately could have taken on some of our workload and shake things up a bit in the leadership team, we had lost a lot of time and energy only to find ourselves back on square one.

Perfect is the enemy of good.

To summarize Part A: We were unable to add a third manager to the leadership team in time to take some pressure off the CEO and allow him to focus on his job. There were very few but yet well-qualified candidates available—hiring one of them and living with the subsequent imperfections would have been the better alternative than not having enough hands on deck to begin with.

Part B: Loyalty Is Valuable Only If Not Guaranteed ¶

If the CEO was lacking trust and micromanaging affairs that were not his responsibility, what about the other managing co-founder—me? What did I do about it?

At first, to be honest, nothing at all. It undeniably helps in the short term if someone more experienced and more successful steps in and immediately corrects a mistake made by someone on the team. On some occasions, the beneficiary of the intervention was me and I was glad about someone having my back.

There was more to it than that, though: The previous years of professional collaboration in the joint project and the jobs that resulted in the new company had taught me one thing: My loyalty to the CEO was a positive ingredient to our stability and success. Me reinforcing the CEO’s positions and actions with my authority and credibility had helped overcome speed bumps on countless occasions, especially in times of uncertainty and adversity—so I stuck to it on purpose. Why change what had been successful, especially if it means being loyal to a very good friend?

In retrospect, however, the issue with my loyalty was that I did not actively manage it enough. It did not have to be constantly re-earned; my loyalty was already mostly guaranteed.

I remember the time when I briefly thought about quitting because we were not making the necessary progress in the growth of the management team to handle the growing pressure. Leaving would have forced a change in leadership. However, I was concerned that such a decision would have triggered a chain reaction detrimental to the company and the CEO. If in my opinion, the best chance of survival for the company was to extend the existing management team, leaving was not an option. Maybe I am overestimating my value but I think that my abilities to provide some stability amidst the constant change and to balance out some of my business partner’s perfectionism with my pragmatism had been essential up to this point. Using a basketball reference, I considered myself being the glue guy on the team. Given the hard time we had to find outside candidates, I speculated (and still do) that my replacement would have been someone with an even closer relationship to the CEO: his spouse. As explained earlier, the already close/d relationship in the management team appeared to be a large part of the problem.

So I stayed and did not make a big fuss about it; I remained loyal and saw it through to the very end.

The effect of this was huge—as much as I can tell now. My guaranteed loyalty took away my function as the CEO’s sparring partner. I would challenge him not enough anymore on his ideas and actions. He would start to decide important things without consulting me first, assuming I would be OK with them—like I had been most of the time. I would not look close enough anymore and observe in detail what was happening around me. Furthermore, my behavior most certainly discouraged others from stepping up and criticizing the CEO. My most important job was establishing and personally executing a culture where constructive critique against the CEO was accepted—and I failed.

Never let loyalty become a permanent shortcut in your decision making. Put an early expiration date on your loyalty.

There is a double irony to this aspect of loyalty. The first is that there were people that told me what they thought was going wrong in the company. Instead of listening closely and activating my sensors at work, I challenged the criticism: We were too much of a special case as that the usual mechanics from other companies would apply to us. It always was like that and we were successful in the past. Etc.

Listen to your loved ones and give them some credit. They see what you are too blind to.

The second irony is that the CEO probably was too loyal to me as well. His criticism about me not criticizing him enough was not enough—if that makes any sense.

To recap part B: If my business partner’s limited trust posed some difficulties for the company, my abundant loyalty only reinforced them. I was so focused on providing some balance and stability during all of this, that I also effectively masked our deeper issues and established hindering traits in our corporate culture. Instead of constantly challenging the CEO and causing a healthy amount of trouble and dispute, I took the shortcut of (over-) prioritizing loyalty.

Conclusion ¶

It took me three weeks to write this article (actually, this is the second article after I deleted the first, 4.500 words long draft). The challenge was: What do I leave out? In the end, I decided to omit all the details about the actual business and the drama to focus on my main point—but I hope that it still makes sense.

This article’s objective was to look beyond the mere symptoms on the surface and provide a few insights into why our start-up really failed. My theory is that a CEO’s burn-out cannot be the sole reason for the failure of a start-up of 16 people. Look deeper and you will find leadership issues at the core. In our case, it was the mix of two things: A CEO hesitating to trust and lower his standards to let outsiders step in as co-manager. And a CIO sacrificing the necessary opposition and masking the deeper issues out of a false sense of loyalty. The combination of both was, in my opinion, the root cause of our failure.

So here are my main lessons learned from my time as managing co-founder of EntrePreneurs and recommendations on how to avoid the above scenario:

- Start with a fully funded business plan. More often than not the business plan will change anyway, requiring more funds along the way. Succeeding as a start-up in full possession of the initial necessary funds is already difficult enough.

- Know when to start trusting outsiders to (partially) manage your company. Do not wait too long for the perfect candidates; they might never come.

- Be aware of the blinding effect of loyalty. Have and respect your own (transparent) agenda and do not automatically hold back your criticism out of a false sense of hierarchy and loyalty.

- If you think that your business partner is permanently working too hard and risking their fitness in the process, it is your responsibility to establish limits. Escalate to your supervisory board or investors if necessary.

- Be conscious about the implications before teaming up with very good friends to start a business. Do not assume that what has been a successful conscious setup for one business automatically is right for the next endeavor. Actively reflect on the ongoing dynamic of your relationship (maybe even with the help of a coach).

There is at least one more advice in particular—but as it does not fit into a short bullet point, I will save it for another article. Stay tuned.

All in all, I am immensely grateful for the years working at EntrePreneurs and the prior project in the capacity of co-founder and CIO. The passion we all felt and acted on among co-workers, investors, partners and especially clients was amazing. Even though dear people had to go through a lot of uncertainty and substantial investments were lost after we had to close our business—we helped realize relevant, systemic change (see the new law in Lucerne) and positively touched the lives of many people. I would do several things differently today, but I still think it was worth it because we made a big difference.

With this article, I also want to encourage other fellow founders to write about their failures and experiences. For example like Nikki Durkin who first inspired me with her 2014 blog post. Or like all those people who submitted their stories to autopsy.io. In any case: Let us share our knowledge to let others benefit from our mistakes. Tweet me the links to your posts!

Disclaimer ¶

Like all posts in my blog, this article reflects my personal opinion. I hope I found the right balance by providing value to a broader audience while still respecting the people involved. Of course, other ex-EntrePreneurs might maintain different positions on this topic and are welcome to correct any facts that I might have misrepresented.

Michael Schmidle

Founder of PrioMind. Start-up consultant, hobby music producer and blogger. Opinionated about technology, strategy, and leadership. In love with Mexico. This blog reflects my personal views.

Mar 5, 2023 · Oct 6, 2024 · 13min read

Four Criteria for Better Decision Making

While we all face decisions on a daily basis, we often reinvent the wheel in our process of decision making. However, there’s a set of strategic criteria that helps you making robust, fast, and comprehensible choices every time. Continue…

Jun 4, 2022 · 6min read

The Power of Subtractive Thinking

What’s better: more success or less failure? More possibilities or less impossibilities? Let’s take a look at the seemingly pointless question—and discover the surprising answer. Continue…

May 18, 2021 · 6min read

Be an Egoist and Trust Your Team

Let’s take a look at the real reason why we should treat our teams as the adults they are. Spoiler: It’s quite an egoistic reason. Continue…

Jan 15, 2021 · 10min read

S2S: Stairs to Success

For most of us, success depends on the interaction with other human beings. S2S is a simple method that can help you be more successful. I’ll show you how. Continue…