… and other counter-intuitive lessons from working 18 months on developing and executing SRG SSR’s technology strategy.

TL;DR: If you’re in a hurry, you can jump right ahead to the conclusion of this article that summarizes my lessons learned.

For everybody else, I have two yes/no questions to start:

Does a strategy work best when every decision-maker in your organization understands and supports it?

Is it too much to expect every decision-maker in your organization to understand technologies well enough to make the big technology decisions?

If your answers have been yes and yes, you should come to the conclusion that a technology strategy must be high level enough for non-technological decision-makers to understand and support it.

The Determining Factor ¶

Who takes decisions is not a matter of who knows best—but who takes responsibility if it turns out to be the wrong decision. The riskier the decision, the more it’s taken by people who are anything but subject matter experts.

In other words: More often than not, your riskiest technology decisions are routinely taken by non-technological people. So how important is it that they get your technology strategy?

Let’s take it one step further: The real test of any strategy is whether decision-makers apply it under pressure. It’s the time when a strategy is most valuable. (After all, who needs a strategy when everything’s going just fine anyway?) It’s also those moments that prove if your strategy was clear and concise enough to remember even in stressful situations.

The real benchmark for your technology strategy hence is: People without technological background who take the riskiest technological decisions under pressure need to understand and remember it.

Let that sink in for a moment.

Now ask yourself if the technology strategy in your organization meets this benchmark.

It doesn’t? Experts refer to this as the Execution Gap.

The best strategy is worthless if people are unable to execute it when it counts most.

Pure Theory—or Is It? ¶

You might say: Yeah, but…

- Why call it a technology strategy if it hardly talks about technology?

- Why call it a strategy at all if it’s so high level that it’s practically common sense?

I understand your skepticism. As human beings, we pride ourselves a lot in our work and the fact that it can’t be done by just anyone. It takes a moment to realize that you have to put in hard work to develop something so beautifully simple that it appears like anyone could come up with it.

Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.

Leonardo da Vinci

Let me encourage you to take the risk of having your work appear overly simplistic: At the Swiss Broadcast Corporation SRG SSR, the approach of simplifying helped to (at least partially) narrow the execution gap.

Here’s how it works for us: compress, ask 2+1, gamify.

A) Compress ¶

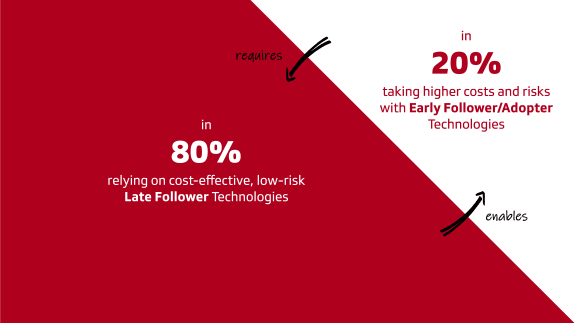

However short your strategy document is, it’s probably still too long. Radically reduce it to its core messages. For example, we compressed our (few pages long) document down to these main statements:

That’s it, the core of our technology strategy. Quite non-technological, if you ask me.

We answered two general questions: “What are we trying to achieve?” and “How do we plan to achieve it?” (Of course, “Why is it worth trying?” is the most important question. It should be answered in the context of the overall corporate strategy though.)

Appears simple enough, doesn’t it? At any rate, it’s possible to deliver this essence in a short pitch.

What’s left is to reiterate these core messages at every opportunity on every channel. If people start responding with And how I am supposed to implement this in my work?

you’ve made a huge step in closing the execution gap.

B) Ask 2+1 ¶

Now that you’ve laid out the foundation and get responses from your target audience, you can start talking about the strategic decision criteria.

In our case, we need to offer criteria to decide: When do we prioritize cost savings, when Digital Transformation? When do we insist on late follower technologies, when do we push for early follower/adopter technologies?

We opted for two (2) criteria specific to our industry and particular context—and one (+1) rather global criterion that probably is valid in most industries. This means: Instead of giving case-by-case answers, the strategy asks leading questions:

Criterion 1 ¶

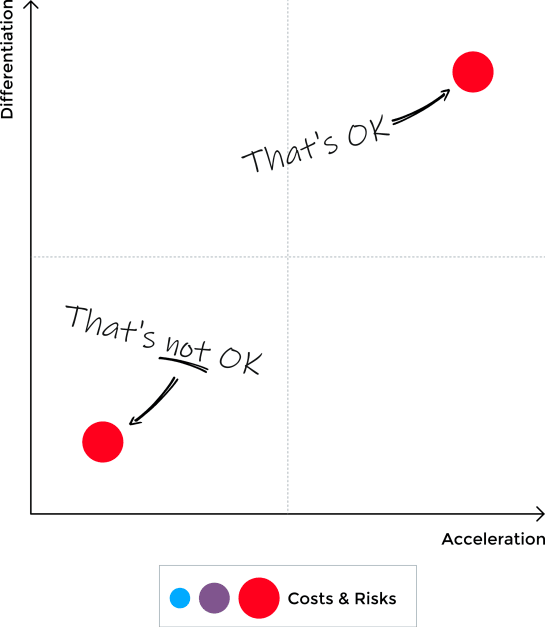

Differentiation: How much does technology X help us to differentiate our offerings in the market?

Criterion 2 ¶

Acceleration: How much does technology X help us to be faster at what we do?

Criterion 3 ¶

Costs and Risks: How high are costs and risks of implementing and operating technology X over its life cycle?

These criteria aren’t independent. There should be a one-way correlation: Of course, low costs and risks are always OK. On the other hand, high costs and risks are OK only in one case:

The great thing about a strategy that asks general questions rather than giving specific answers:

-

It’s still the decision-makers who make the decision and take the responsibility for it. The strategy itself can’t grant any exceptions when necessary. It supports decision-makers; it doesn’t replace them. Remember, that’s why we try to keep our technology strategy as non-technological as possible in the first place!

-

The strategy is transferable to many scenarios. Not just the ones you foresaw; also the ones you never envisioned. Professor Albert Einstein once was asked:

Why did you let your students take the same exam as the semester before? Aren’t the questions the same?

He famously answered:Yes. But the answers have changed.

C) Gamify ¶

With all the activities so far, our strategy hopefully is clearer, more memorable, and more transferable. Now let’s make it more actionable.

What we need is…

… a game!

Or at least, we need a simple process that takes the strategy’s general questions and turns them, case-by-case, into good answers and largely good decisions.

To that end, we’ve adapted a method named Priority Poker and developed a game we call “Strategy in Action”. Priority Poker is used to align a group of people on priorities. For each item to prioritize, people choose a card with a number on a scale (i.e. 8 out of 10) that represents the subjective importance of the item, then disclose their number all at the same time. There are two possible outcomes:

- If everybody has picked the same number, the group is already aligned. They put their cards back in their decks, move on to the next item to prioritize, and again choose a card.

- Whenever people pick different numbers, they explain to each other the reasons behind their choice. Once all pros and cons of the most extreme picks have been shared, the group starts over with selecting cards/numbers. At this point, the group begins to align and extremes will converge, at some point ending around the same number on the scale.

In the end, all items on the list received a number or priority as worked out by the group.

Priority Poker allows all people in a group to share their facts, experience, opinions, etc. Individuals will learn about perspectives or arguments they didn’t think of before. As a result, people will correct or confirm their assessments, causing the group to align more and more—and finally agree on a set of shared priorities. (Read more about Priority Poker and how to harness collective intelligence.)

Here’s how our adaptation works:

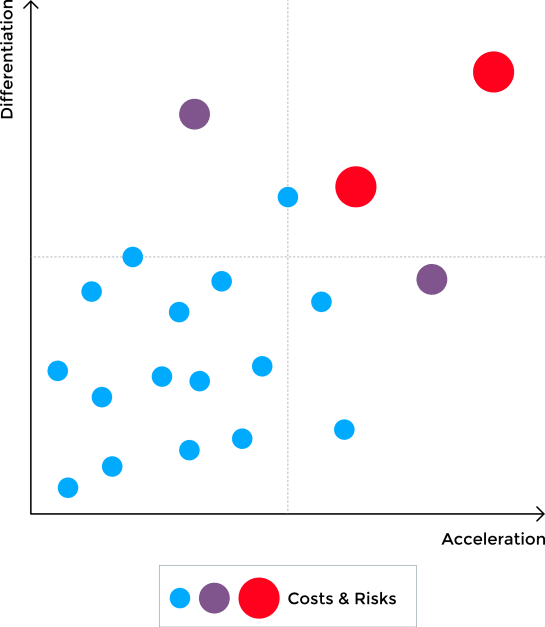

- Poker about what a given project requires in terms of the decision criteria (differentiation and acceleration).

- Poker about what a set of potential technologies deliver in terms of the project’s requirements.

- Finally, poker about what the same technologies entail in terms of costs and risks.

At the end of the game, the group will be able to collectively determine which technologies are the best strategic fit for the given project: the one that meets the minimum differentiation and acceleration requirements—and brings the lowest costs and risks to the organization.

If the entire organization implements this approach, by and large, two things will happen:

- High technology costs and risks will concentrate on projects with high requirements to differentiate and accelerate.

- Projects with low differentiation and acceleration requirements will be optimized for low technology costs and risks.

And that’s the strategy!

Interesting Findings From Playing Strategy in Action at SRG SSR ¶

The format Strategy in Action is still pretty much in its early stage. Yet, after having played the game on different occasions, we already found some interesting aspects I’d like to briefly share.

In most sessions, there were several Aha!

moments. People dramatically changed their initial assessment of project requirements or potential technologies based on what was just revealed by others in the group. It became painfully obvious that the only way to know what others think is to take the time to talk about it. While the quality of strategic decisions will improve with this format, it first and foremost improves the understanding and hence commitment to the decisions.

Also, once we played the game about the same project and the same potential technologies at the same time in three different and diverse groups. Interestingly, they all came up with the same result which technology was the best strategic fit.

I might write a separate article as we continue to refine the game and gain more insights.

The Role of Trust ¶

Developing a clearer, more memorable, more transferable, and more actionable strategy is investing a lot of resources into a tool. If you think back at decision-makers under pressure (like the kid lost in the maze), one important ingredient for a successful strategy is still missing: trust. In addition to understanding and remembering the strategy in all sorts of situations, people also have to trust that it’s the right strategy before they can apply it.

Trust, however, is based on people, not tools.

So as a professional strategist, don’t forget to invest equal resources into building trust and relationships with decision-makers (experts and laymen alike). If they trust you, they’ll be more inclined to trust the strategy that you’ve developed—and apply it when the time comes without having second thoughts.

When the trust account is high, communication is easy, instant, and effective.

Stephen R. Covey

Conclusion ¶

In this article, I shared a few lessons from my work on the SRG SSR technology strategy.

The rather obvious main lesson is this: It’s both the card and the player who win poker games. (I’m referring to the real poker game here, the one where players have to cope with incomplete information—just as companies and their decision-makers do in their environments.)

You need to have the right strategy. Having the wrong strategy perfectly executed will still be a failure.

You also need to have a strategy that can be applied by decision-makers. Having the perfect strategy will still be a failure if people are unable to execute it.

The more counter-intuitive lessons are:

-

In large parts, a technology strategy serves a non-technological audience and hence shouldn’t focus on specific technologies.

-

Any strategy completely depends on the people who’re supposed to execute it, when they’re supposed to execute it. To enable decision-makers in stressful moments that count most, a strategy needs to be clear, memorable, transferable, and actionable.

-

Many people expect a strategy to deliver specific answers. Don’t fall into this trap! A strategy that gives specific answers is tailored to specific situations only. If you want a strategy that is transferable to all kinds of situations, ask questions instead. After all, a strategy is supposed to support decision-makers, not to replace them.

-

Develop strategies like products. Test them with real users, then iterate based on the insights you gained. Map the journey of your customers. Your strategy is more than a document; bundle it with all sorts of communication tools. Design and gamify the user experience. The list goes on!

-

People will take your strategy only as seriously as they take you. The level of trust people put in your strategy will benefit from the trust people put in you as a person and as a team.

Our team is about to start the work on SRG SSR’s distribution strategy. We’ll be applying our lessons learned—and will continue to learn a lot more!

Michael Schmidle

Founder of PrioMind. Start-up consultant, hobby music producer and blogger. Opinionated about technology, strategy, and leadership. In love with Mexico. This blog reflects my personal views.

Oct 6, 2024 · 4min read

Revolutionizing Decision-Making

Last year, I shared a simple framework for making better decisions. Little did I know it would spark a journey that led to creating PrioMind, an app that’s revolutionizing how we approach choices. Here’s the story of how four criteria evolved into a powerful decision-making tool, and what I’ve learned along the way. Continue…

Mar 5, 2023 · Oct 6, 2024 · 13min read

Four Criteria for Better Decision Making

While we all face decisions on a daily basis, we often reinvent the wheel in our process of decision making. However, there’s a set of strategic criteria that helps you making robust, fast, and comprehensible choices every time. Continue…

Sep 12, 2021 · 6min read

Applying Design Thinking to a Pandemic

Everybody seems to have strong opinions about the best way to get out of the COVID-19 pandemic—to the point that makes it really tough to, indeed, get out. Maybe Design Thinking can help? Continue…

Apr 4, 2023 · 5min read

The True Challenge of the AI Alignment Problem

AI is a big topic these days. One reason for this is the fear of AIs acting against human values, potentially causing severe consequences. However, there’s an even bigger challenge than aligning AIs: Let’s look in the mirror. Continue…