The Antiquated Form of the World’s Most Innovative Companies

Apr 5, 2018 · 12min read

Adults regularly vote on the most important matters of government—yet at work, they accept having usually little to no decision-making power. How come?

Over eight years ago, I moved to Switzerland—a country with one of the most direct democracies in the world. This political system means that the Swiss citizens are regularly asked to vote on all kinds of governmental matters. Instead of only casting their votes every few years to elect their leaders, the Swiss adults usually receive once per quarter an invitation to vote on very specific subject matters. These matters can relate to federal, cantonal (i.e. state), or municipal issues.

In addition to being able to vote on such matters, Swiss adults also can put to the vote whatever issue they want to bring forward (given that a certain limit of people supports the initiative or referendum). In other words: The Swiss do not only answer the questions regularly asked by their government—they even ask their questions to be answered by the people.

Requirements and Returns of Swiss Direct Democracy ¶

What It Takes … ¶

This level of political activity requires that the Swiss citizens are well educated and well-informed about all matters it is asked to vote on. A foreigner might think that it is almost impossible to get enough people interested in politics, let alone get them to know and understand the intricacies of political issues. Even for me, being a close neighbor coming from just across the Swiss-German border, it seemed like a very foreign concept indeed.

Of course, the Swiss government needs to edit and send extensive in-depth documentation to each voter in preparation for every voting. In terms of mindset, the Swiss are required to own their political responsibility. Since they have not outsourced their important political decisions to their leaders, they need to deem it their duty to get involved, get informed, and finally come to an educated decision. It takes a strong cultural trait—which they possess, however.

… and What It Gives ¶

Many conversations of everyday life center around political topics. People intensely debate about upcoming votes with their colleagues, friends, and families. At first, I was surprised about the level of depth and intensity of these discussions. In Germany, political discussions among co-workers, friends, or family were rare and superficial at best. Not so for the Swiss: The extensive discourse helps them form their opinions and feel ready to take decisions that can have a profound impact on millions of people.

Having already taken many decisions in the past (the Swiss have been called to the ballot 306 times since 1848, each time voting on a variety of issues) and hence being largely co-responsible for the current conditions in Switzerland, they are already deeply invested in their political role. There is nobody to blame for large-scale deficits but themselves—they feel accountable. Since the Swiss system allows them to easily address even smaller concerns, people largely refrain from playing the blame game and instead invent and propose ideas. They take matters into their own hands and actively shape the future of Switzerland. As a result, the Swiss deeply identify with their country in the long-term. In my opinion, it also leads to well-thought-out and sound decisions that are of very high long-term quality (meaning there are fewer revisions and course corrections necessary in the future).

Business Is Business ¶

What completely boggles my mind is the fact that at work, the Swiss are no different than any other Western society: Whether they work in privately owned businesses or public-service offices, they leave democracy at the door before starting their work. A minority of executives decide what the majority of employees have to do daily. Whatever the Swiss citizens believe is the best way to govern their nation, canton, or municipality, they apply a completely different approach in their professional lives. Whether they have a boss or are a boss in their organization, they give almost all power to that role.

Take a minute to appreciate this: Several times per year on a Sunday, the average Swiss citizen votes on issues like taxes, insurances, public transportation, military, etc.—affecting their entire nation of over eight million inhabitants. Then, the day after, they return to the office to execute the orders from their top management in which the large majority has no say whatsoever. We can talk about the reasons and the dis-/advantages of this in a minute—but I find it almost schizophrenic how the Swiss treat themselves as accountable adults when taking the decisions of utmost importance and impact while accepting to be treated as irresponsible minors that require close supervision when it comes to even minor business decisions. Especially, since most of us feel that something is fundamentally wrong with this approach in today’s world.

In addition to this stark contrast in Switzerland, we can observe similar contradictions elsewhere in the world. There are many organizations that we consider the most innovative in terms of goods and services that they offer. Think of the big tech companies like Apple and Google: Would you agree that they are among the most innovative companies on this planet? No doubt (at least if you look at the goods and services they offer to their customers)! Yet we can observe that their organizational structures and hierarchies still follow models that are many decades old. Apple, Google, and even the hottest start-ups in Silicon Valley, Israel, or China implement antiquated organizational forms.

That does not make any sense. Why is that?

Democratic Companies Do Not Stand a Chance—Right? ¶

Governing an entire nation seems to be fundamentally different from governing a company. Businesses should be lean and agile to react as fast as possible to changing markets and customer demands. Right? They cannot afford lengthy processes of listening to their employees’ concerns, have them educated in detail and vote on all the fundamental issues. Instead, businesses can be thought of as armies: Just a minority of generals understand the big picture and give the orders while the rest of the soldiers execute those orders swiftly and without question. Correct? Or have you ever heard of an army where soldiers were asked first to vote whether to go to battle and on the tactics for each battle? Time is money.

Then again, our economy seems to follow different rules than the military does. Or have you ever heard of a navy where admirals were decorated for leaving men behind who failed in their mission? Yet the leaders of our companies receive bonuses and rewards for abandoning parts of their crew that did not reach their goals.

Time to ask someone who can tell us what is wrong and what would be right to do as a business.

Popular Misconceptions of Running a Business ¶

Game Theory distinguishes between two types of strategic situations that individuals, teams, or organizations find themselves in. According to this theory, there are finite and infinite games.

In finite games, all players have agreed to a set of rules that clearly define when the game ends (hence the name “finite”) as well as how to participate in and win the game. The objective is to win the game in the given time frame. Sports like basketball or tennis are such finite games.

In infinite games on the other hand, there is no predefined end (hence the name “infinite”) and the rules as well as participants are unknown and constantly change. The objective of these games is to keep playing. Doing business is considered an infinite game: Anyone can join or leave the game at any time, and the rules can unpredictably change from one day to the next (not just laws—but i.e. shifts in the behavior of consumers, or investors).

Simon Sinek does a better job describing Game Theory than I ever could in the video below:

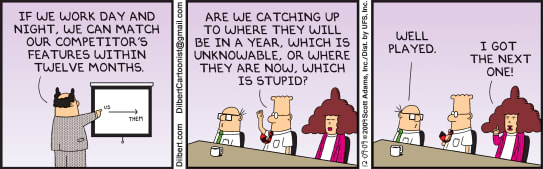

He rightfully points out that most companies do not understand that they are playing an infinite game. Usually, companies act like they would play some finite game by “beating the competition”, “being a market leader”, or “winning the race”.

In my experience, this assessment is spot on: Companies usually focus a lot on their current competitors as well as on short-term gains when making decisions. They rarely decide based on their values and vision if that could result in short-term setbacks.

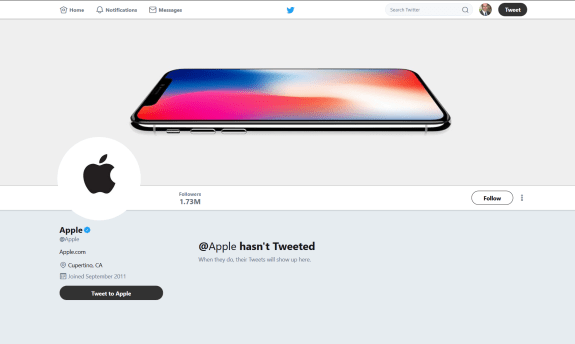

According to Simon Sinek, one notable exception is Apple, Inc. As the currently most valuable company in terms of the stock price, they have more to lose than any other company in the world. Yet they ignore their competition. The fact that Apple is inactive on social media (see example below), seems to prove how little they care about the outside noise. At Apple, they consistently follow their values and vision. They stay true to what they believe and no outside impulse will ever drive them to do anything that is out of character for Apple.

Alright, so basically only very few companies realize which game they play. Most pursue the wrong objective and are governed by the wrong rules. The few frustrate the many by not obeying the imaginary rules of a seemingly finite game.

This answers the difference that usually exists (but should not exist) between companies and the military. Still, I have some open questions left.

The Apple Paradox ¶

Let me stick to the example of Apple as one of the few companies that have understood the strategic situation they are in. And I agree: They seem to be more driven by their long-term values and vision than by short-term gains. They are very consistent and predictable in their behavior.

Having that said: Apple is no different than most other major companies in terms of their organizational structure. They follow a strongly hierarchical top-to-bottom chain of command in which supervisors take the decisions for their subordinates that only can be overruled by the supervisors’ supervisors. The most important decisions at Apple are taken by very few individuals only and carried out by the rest of the employees (even though these decisions seem less erratic than elsewhere).

It makes me wonder why a company like Apple, Inc. is ahead of the curve regarding product innovation and value-based decision making—and yet implements such an archaic organizational form. Why does Apple not tap into the power of a more democratic decision making and sharing of responsibilities? Apple always has taken its time to come up with the best possible product; they never rush something out the door if they feel they could do better. They should be able to improve their organizational structure, too.

The Limits of Classic Management ¶

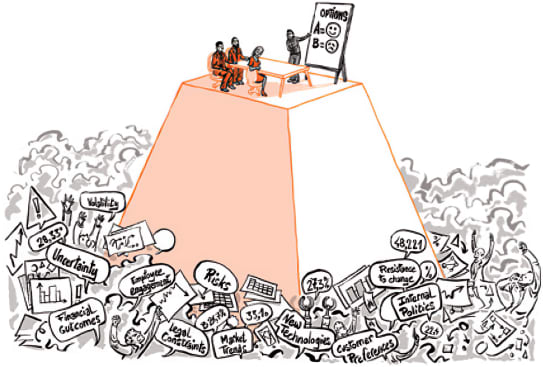

In his book “Reinventing Organizations”, Frederic Laloux perfectly captures why people feel that our current way of managing organizations has reached its limits. He observes that the complexity in an ever-increasingly interconnected world exceeds the capacity even of top managers: “The few people at the top, however smart they are, don’t have enough bandwidth to grasp and deal with all the complexity.”

I think most of us can relate to the following illustration: “Since you only have three minutes to make this critical decision, I’ll just share a few sound bites … and then we’ll all pretend you understand the implications of your decision.”

However, Frederic Laloux can take away one positive aspect from his research:

The pain we feel is the pain of something old that is dying … while something new is waiting to be born.

Frederic Laloux, Reinventing Organizations

The Light at the End of the Tunnel ¶

Can companies be at all managed differently (meaning: in a more contemporary way)? Let me quote his answer:

Well, it turns out that it absolutely can be done—there are a number of truly outstanding organizations that already operate from the next stage.

Frederic Laloux, Reinventing Organizations

Then why do many organizations still rely on antiquated forms?

Deep down, they would love to function without the [hierarchical] pyramid, without the need for bosses. But they haven’t found a way to do it in practice.

Frederic Laloux, Reinventing Organizations

So, what would be a serious example of a company that works well without having superiors and where responsibility is shared among all employees?

Get ready for this: at Buurtzorg with its 9,000 people, no one is the boss of anyone else.

Frederic Laloux, Reinventing Organizations

Wow. Mind you: Buurtzorg is in business for ten years now and profitable.

On top of it all, Ernst & Young documented savings of around 40 percent to the Dutch health care system thanks to Buurtzorg. 40%? Wow again. As if the positive internal impact on the happiness and wellbeing of their employees was not enough—they even make a huge positive difference for their environment. And there are more organizations like this: radically different but still successful by today’s standards. This really could be the beginning of something new.

Reinventing the Swiss Broadcast Corporation (SRG SSR) ¶

In March 2018, just a few weeks back, the Swiss people voted on the abolishment of public-service broadcast fees. While the people clearly dismissed the initiative, a lot of criticism about the Swiss Broadcast Corporation (SRG SSR) was expressed during the preceding debate, and rightfully so. I can attest from my insider perspective that we have a lot of room for improvement. The organization must reinvent itself over the coming months and years to stay (or again become) relevant enough among the public to keep playing the infinite game and to stay in business.

This reinvention process has been anticipated in various parts of the organization. The CTO’s department (in which I work) created a new team called “Digital Innovation” at the end of 2017. I joined that team. As the name suggests, our responsibility is to accelerate the digital transformation of the company—which first and foremost requires a change in culture and mindset rather than technology.

During my three years at SRG SSR, I have encountered many colleagues with great ideas, a lot of passion for our business and a deep sense of responsibility regarding our public funds. It both frustrates and drives me that the structure and processes of the company do not promote such ideas and efforts. But this is the reason our team exists: to induce change for the better.

I am curious to see where our efforts will lead us. Regardless of the outcome, it will be a very interesting journey. I will keep you posted.

Michael Schmidle

Founder of PrioMind. Start-up consultant, hobby music producer and blogger. Opinionated about strategy, leadership, and media. In love with Mexico. This blog reflects my personal views.

Jun 4, 2022 · 6min read

The Power of Subtractive Thinking

What’s better: more success or less failure? More possibilities or less impossibilities? Let’s take a look at the seemingly pointless question—and discover the surprising answer. Continue…

Feb 6, 2022 · 6min read

A Visualization of Leadership

Recently, I came across a helpful visualization of what Leadership means in times of Digital Transformation. Let me show you. Continue…

Oct 11, 2021 · 6min read

The Best of Both VUCAs

Ever heard of VUCA—as in: Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity? Ever thought that these aspects could actually be beneficial on a certain level? Let’s find out. Continue…

Sep 12, 2021 · 6min read

Applying Design Thinking to a Pandemic

Everybody seems to have strong opinions about the best way to get out of the COVID-19 pandemic—to the point that makes it really tough to, indeed, get out. Maybe Design Thinking can help? Continue…